Governments around the world have responded to the COVID-19 pandemic with WASH and health measures. International actors have been working to make sure these two sets of measures are better connected.

The unprecedented response to the COVID-19 pandemic has included widespread messaging, unprecedented itself in terms of scale, about the importance of handwashing. “It is clear that frequent and correct hand hygiene is one of the most important measures to prevent infection with the COVID-19 virus,” said Juste Hermann Nansi, Country Director Burkina Faso with IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre, speaking during IWA’s recent online discussion on the pandemic and vulnerable communities.

Hand hygiene forms part of the wider area of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). “WASH is central to the COVID-19 response and recovery efforts,” added Maggie Montgomery, Technical Officer, World Health Organization (WHO). “It is fundamental to containing the spread, and hand hygiene is critical.”

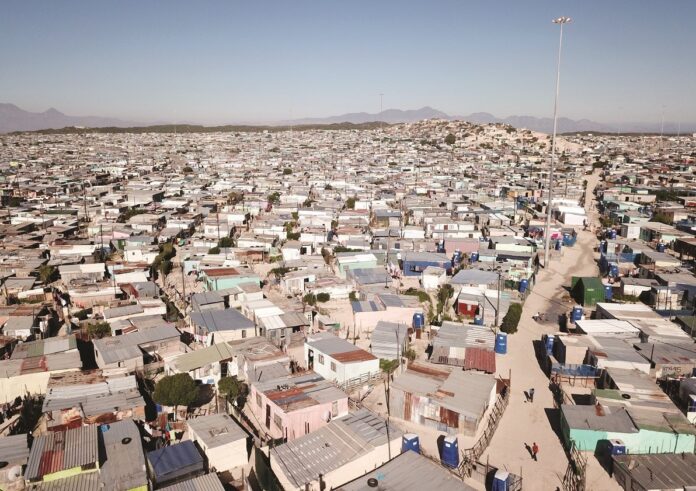

This is particularly of concern for vulnerable communities, such as those in informal urban settlements in developing countries, that do not have ready access to WASH facilities, especially clean water.

“This pandemic is showing just how essential WASH is to ensuring the health of our most vulnerable communities. It is impossible to keep people safe if they don’t have access to water, sanitation and hygiene services and supplies,” said Brian Arbogast, who is Director of the Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Programme at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The access gap

Set against this fundamental importance of WASH are the huge global deficiencies in lack of access to the different aspects of WASH, which make for familiar reading. It is an extension of the story of the struggle to achieve progress with UN Sustainable Development Goal 6 on water. A few statistics highlight the scale of concern in the current pandemic.

IRC’s Nansi noted that only 24% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa has access to a safely managed water service – safe water on the premises available when needed. “Basically, these are the only ones able to comply with the rule of frequent handwashing,” he said. “Put another way, it is hard to expect the adoption of regular handwashing by 76% of the population in sub-Saharan Africa.”

Basic hygiene is not just about water – it is about soap, too. “At the global level, three billion people are lacking soap and water at home,” said Nansi. “When talking about vulnerable communities, this is the key number we should have in mind – the challenge is enormous.”

Pandemic action

Given these needs, national responses to the COVID-19 pandemic have included local practical action, such as setting up handwashing stations. The need for rapid action has spurred efforts to take different approaches. “Spontaneously across the world, in many countries, people have come forward to fight COVID-19 and counter the challenges with local innovations and technologies,” said Puneet Kumar Srivastava, Urban WASH Adviser (Utilities), WaterAid UK.

“The foot-operated handwashing stations that WaterAid and many other organisations have been promoting, based on local innovations by the people living in poorer settlements, and providing more handwashing community points and promoting [handwashing] at the household level – I think that needs to be encouraged overall to fight this challenge,” he said.

The need for soap requires action at a practical level, as Eunice Ubomba-Jaswa, Research Manager (Water Resources Quality & Management) at South Africa’s Water Research Commission, noted. “For the pandemic, one thing that has really come up is this need to provide innovations that have soap and water together – instead of just providing the water,” she said. “It has to come with the soap – and, then, what to do with the waste afterwards.”

At the same time, the value of such practical options depends very much on whether or not people want or understand the need to practise good hygiene. The widespread handwashing messaging seen around COVID-19 aims, of course, to promote this.

“We have a population that is serviced very well. At the same time, we also have a population that does not have access,” said Ubomba-Jaswa. “You get behavioural change when people understand what is going on. For microorganisms, that is very difficult, because people don’t see them – that’s the bottom line.”

“In all our messaging, we stressed the fact that this pandemic has brought to light the need for WASH services,” she continued, adding: “We always needed it.” Importantly, in the current pandemic it is clearer that, if access is lacking, this has implications for the wider population because of the potential for this to contribute to the spread of the disease. “It affects all of us, as the public,” she said, adding that this aspect of the messaging represents a wake-up call.

Messaging has been important for WaterAid, too. Srivastava explained that there was clearly a need to support country programmes in developing science-based messages, adding in wider aspects such as social distancing. “That was the immediate response from the organisation,” he said.

Srivastava agrees on the need for messaging to make clear that WASH is a matter for everyone, whether or not an individual has good access themselves. “If anybody in a city is at risk of infection, the rest of the city is not safe,” he said.

International response

The WASH gap, and its important place in the COVID-19 pandemic, has prompted a range of actions from the international community. These have included WHO taking a lead in creating the COVID-19 Solidarity Response Fund. As of mid-June, this had raised or committed more than $222m from approaching half a million individuals, companies and philanthropies. At WHO’s request, the Fund has also disbursed money to UNICEF for its work on COVID-19, including to support vulnerable countries by providing access to water, sanitation and hygiene, and basic infection prevention and control measures. Other initiatives include the world leaders’ call for action on WASH and COVID-19, initiated by Sanitation and Water for All.

WHO has stepped up its own action, too – specifically on hand hygiene. This year, it dedicated its annual health worker call for action, on 5 May, to a ‘Clean care is in your hands’ campaign, aimed at nurses and midwives. It also issued interim guidance on 1 April recommending that countries improve hand hygiene practices to help prevent COVID-19 transmission by “providing universal access to public hand hygiene stations and making their use obligatory on entering and leaving any public or private commercial building and any public transport facility”. Its COVID-19 Strategy Update of mid-April highlights the importance of handwashing.

Beyond WASH

As important as these activities are, wider connections are key, too. The practical measures being taken should be seen as a foundation for the future. “We need to look at, and set new benchmarks for, communal WASH services during the pandemic, and systematically work towards making it the new normal for pandemic resilience,” said Srivastava, who highlighted the importance of improvements in overall systems and human rights-based approaches.

Inclusion of the WASH-related messages in WHO’s COVID-19 Strategy Update sets them in a broader context. This helps raise awareness of the contribution WASH can make in the wider health picture, especially given the relatively high cost benefit of hand hygiene benefits compared to other types of intervention.

“COVID-19 response policies need to explicitly link inclusive water, sanitation and hygiene – meaning it reaches all communities,” said Arbogast. “They must link WASH to public health, and so should general health and emergency response policies, even beyond COVID-19.”

Arbogast noted that vulnerable communities are not typically reached by networked services, and that water and sanitation services for most of the poor and vulnerable are provided by small-scale operators. “These operators must be prioritised as critical service providers,” he said, adding that they should be “supported and subsidised just as other essential services and the water and sanitation utilities are”. Similarly, the lack of networks in these areas means faecal sludge management services and open drains should be included in the emerging opportunities around wastewater-based epidemiology and surveillance approaches, he added.

“WASH is incredibly central to the COVID-19 response and recovery efforts,” said WHO’s Montgomery. This is what underpins the value of the WASH leaders statement, for example. “It is really meant to shake things up, to remind people that WASH is critical for COVID and it is critical for a lot of other reasons,” she said. “All national COVID plans should make sure that WASH is budgeted, monitored, and part of the greater efforts to control and prevent.”

This call for WASH to be better connected reflects the lesson learned by the WASH sector that sustainable services can only be achieved if the whole system of stakeholders and institutional arrangements, for example, are in place and functioning.

This applies just as much to the latest action on hand hygiene. “Sustainability is always a huge challenge, and that is the same for hand hygiene,” said Montgomery. “We have to make sure we put the systems in place, and the supply chains and the people, to make sure they are sustained and, obviously, adequately used.”

An opportunity for the future

IRC’s Juste Nansi acknowledged the stark implications exposed by the pandemic but sees an opportunity to work for the future.

“I am afraid there is not much we can realistically do during the emergency to meaningfully make safe water available every day, endlessly, for 16 million people – [the] 80% of the population in my country, Burkina Faso, who live without a safely managed household connection,” he said.

The focus of IRC, therefore, is to prepare for future pandemics and emergencies. “We need to transform the positioning of WASH services in national and global development agendas as a legacy of COVID-19,” he said.

This needs high-level political attention, but there are clear needs at the implementation level. “We need to take this opportunity to insist, more than ever, on a closer coordination between health and the WASH sectors,” added Nansi. “If there is one thing we believe, that COVID-19 has taught us, is that the health response is a WASH response. That is the message we need all together to send to policymakers and donors.”

Arbogast summed up this opportunity around the current focus on WASH and COVID-19. “Mass action to accelerate access in handwashing is needed to scale up hygiene behaviour dramatically in the face of COVID-19,” he said. “We have the opportunity to make investments during this next year that will continue to deliver benefits that save lives long after COVID-19 has passed. But this won’t happen unless there are very robust investments in WASH at all levels of the response.”

Article based on comments made during ‘COVID-19: WASH in Vulnerable Communities’,

iwa-network.org/learn/covid-19-wash-in-vulnerable-communities, held 12 May 2020.

Reporting by Keith Hayward